Innovations — Searching for a New Descriptive Language

TL;DR: Our approach to innovations is incorrect, leading to futile research. Let’s adopt a more suitable language for describing and researching innovations, and everything will fall into place.

Disruptive Innovations

When we talk about innovation, something grand immediately comes to mind. In popular culture, a startup founder is always someone aiming to change the world. In product development culture, the concept of “disruptive innovation” — an innovation that fundamentally changes the market — remains alive and well. It is contrasted with “sustaining innovation,” which merely improves existing products.

The term “Disruptive Innovation” was popularized by Clayton Christensen in his article “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave." The article discusses the evolution of product characteristics and how companies respond to this evolution. He argues that the development of a specific technical attribute (e.g., sound quality in radios) often reaches the limits of current technology. Technologies that prioritize seemingly less important attributes at the expense of the primary ones become “disruptive,” creating new markets and applications. For instance, Sony sacrificed sound quality to create portable radios. Thus, the article concludes that companies should pay less attention to user preferences and more to technologies that seem misaligned with those needs. New technologies create new markets and new users.

This idea makes sense when talking about technology. However, product owners often transfer this understanding from the technological realm to the semantic realm. We assume that the right product radically alters established habits. Examples like Amazon, Netflix, and Twitter are often cited as having upended many familiar practices. If people can’t accurately predict the technical features they need, then their habits and opinions can also be ignored — they’ll adapt.

In reality, it’s the opposite. A product or technology is never the source of behavioral change. The better a product integrates into our existing consumption patterns, the more it adapts to and fits our needs, the more likely it is to create a “market revolution.” Misunderstanding this leads us to extend the principle of disruptive innovation from product attributes into the very life of potential users.

A popular (though dubious) quote attributed to Henry Ford illustrates this point: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said, ‘a faster horse.'” What’s often overlooked is that even if Ford didn’t literally create a faster horse, he still relied on existing habits around machinery. For example, early tractors weren’t just vehicles; they also powered various farming operations. Cars seamlessly integrated into everyday life, and only later did society evolve new patterns that spurred further automotive development.

If we examine our own experience with digital technology, we’ll find that the cause-and-effect relationship is cyclical, not linear. It’s not “product → behavior” but “behavior → product → behavior.” Instagram didn’t teach people to post or edit photos online. It simplified an action people were already doing. Then users adapted the product to their existing habits, and only after that did the practice of photo posting evolve.

Human habits and communication patterns are the biggest sources of innovation, not the other way around. For innovation to succeed, it shouldn’t change lives; at first, it must integrate into them.

The Tragedy of the Milkshake

A simple example from my life: in my bedroom, there’s a heater. It’s internet-connected and comes with a remote control. Obviously, the remote is more convenient than a smartphone app — you just reach over and press a button. In contrast, using the phone requires opening the app, selecting the heater, and then turning it on.

But I’ve noticed a pattern: when I’m in bed before sleep, I turn on the heater using my phone instead of the more straightforward remote lying right next to me. Why? The answer is simple: my phone is always in my hand. The smartphone is an extension of myself, making it easier to click a few buttons than to switch contexts to a separate device. Using the phone integrates better into my daily life than the seemingly more convenient remote.

Ignoring the context of product usage can lead to seemingly logical, beneficial decisions that ultimately fail to gain popularity. Users would need to adapt too much to use such solutions. New products and features should act like a missing puzzle piece, seamlessly fitting into the user’s environment. When we aim to make product development revolutionary, we end up forcing users into something unnatural.

This is an obvious thought and is repeatedly emphasized in the Jobs To Be Done (JTBD) framework. One of its popularizers, Christensen, also coined the term “Disruptive Innovations.” JTBD is well-known and widely used, advocating for studying the context of product usage. Yet, based on my experience with its practical application, I believe we often misunderstand its essence — and perhaps even Christensen himself did.

My attitude toward JTBD has shifted over time. At first, I saw it as a trendy buzzword for people unfamiliar with marketing. Then, it grew in my eyes to a product creation framework, a useful metaphor for IT professionals. It establishes its terminology, better describing the structure of human needs for “techies.”

But now I see that JTBD contains a profound intuition about the essence of innovation. It seems Christensen struggled to convey this clearly, and after being distilled through courses and simplifications, JTBD has lost much of its essence for many.

The overused “milkshake case” is particularly illustrative (though later debunked in Jim Kalbach’s Jobs to Be Done Playbook). This case is often cited as an example of innovation that dramatically boosted milkshake sales. I won’t retell it — you can read it here. It seems simple: talk to users, understand what job they’re “hiring” the product for (sometimes even asking directly), and they’ll tell you what features to implement.

In reality, it’s more complex. The habit of eating before work has always existed and will continue, regardless of milkshakes. Milkshakes simplify the act of eating on the way to work with minimal effort. After studying this process, creators realized that thickening the milkshake would make it better suited for this context. Despite its depth, this case is often reduced to, “Just talk to the user, and they’ll tell you what they need.” I find this tragic.

The terms Disruptive Technologies and the milkshake example from JTBD are often interpreted in opposing ways. We’re told not to focus on user needs, yet simultaneously to talk to users so they can tell us what they require.

Resolving the Contradiction

This contradiction arises only when JTBD is misunderstood. Christensen clearly differentiates between “function” and “job.” This may seem like semantics, but the distinction is critical for understanding product usage. The term “job” reflects the fact that users adapt products to themselves, not the other way around.

People don’t engage in forums because forums facilitate interaction. Forums aren’t the source of interaction. People learned to use forums for interaction. While this might sound like the same thing, it’s diametrically opposite from a product development perspective. Instead of inventing a new function to keep users engaged, we must allow users to adapt the product to more of their existing habits. Only then will they use it more frequently.

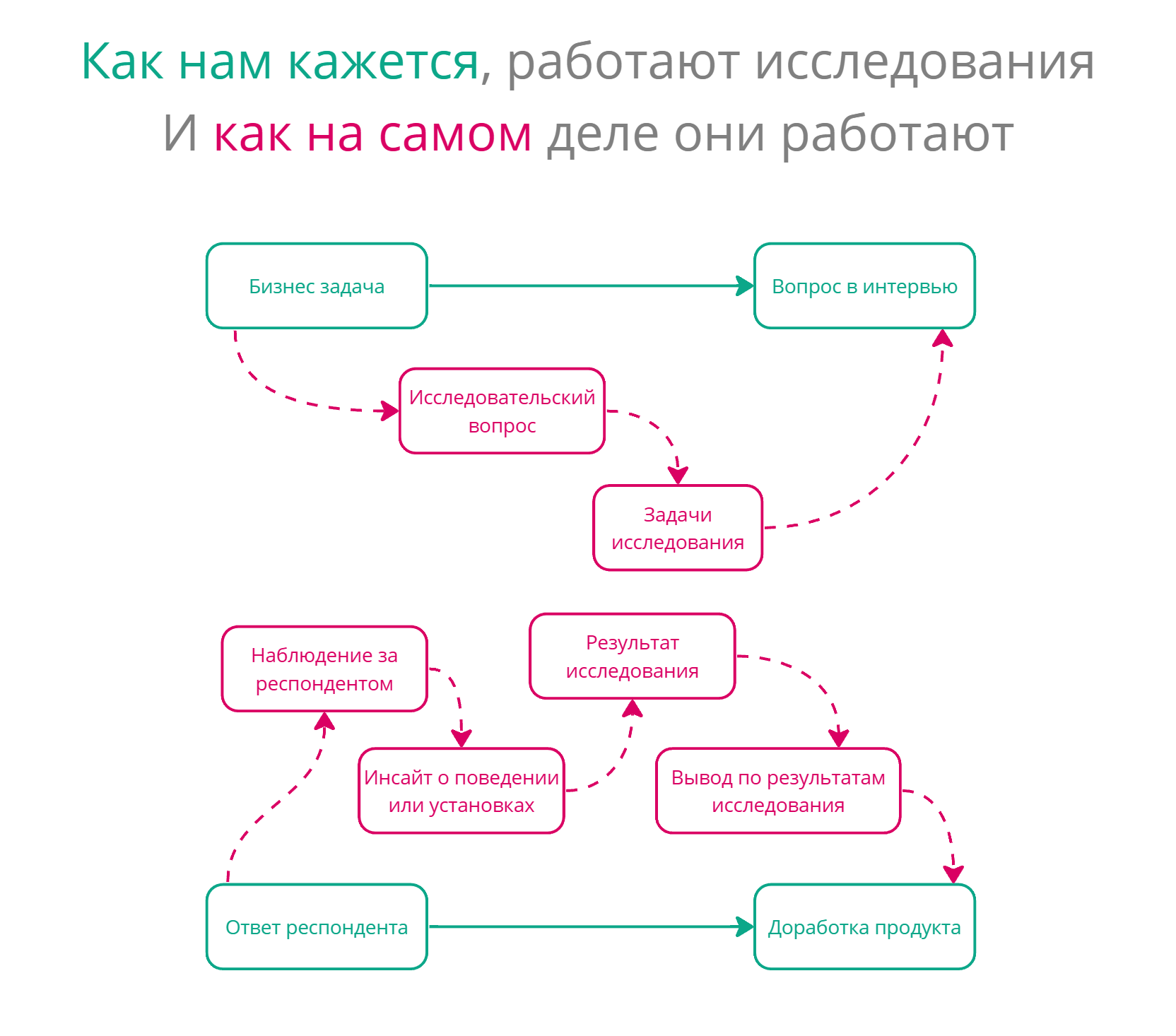

Words are incredibly important. How we talk about something can reveal a lot. For example, a good marker of incorrect attitudes toward research is the phrase “Let the users say what’s better.” Just like with a cocktail, we expect that if we ask the question in the right way, people will say “It should be thicker,” after which we immediately take this to development. And there it is — innovation, growth in metrics, new markets. But in reality, such a direct process doesn’t exist.

Our business task goes through a long and painful process of operationalization. The same happens in reverse — observations turn into insights, insights into conclusions, conclusions into decisions. We do not ask users what we should do and how. By studying people, we identify actions in which using our product can simplify their execution with minimal cost to the user, and each person may have different costs. This is why we conduct research. Reflecting on and understanding why I use my phone instead of a remote control only became possible because, as a researcher, I can look at my behavior from different perspectives. This is my primary skill and bread. And it would be strange to expect such reflexivity from people who don’t engage in studying others’ behavior in their work. By expecting users to reflect on their use of digital products, we are shifting the work of researchers and product owners onto them.

In the everyday understanding of JTBD, this very important nuance is lost. Perhaps because the dichotomy “function/work” is not the best language to describe what’s happening. We think we are working directly with opinions, whereas we need to study behavior. This is where sociology comes to our aid. To come up with a quality innovation, we must study actions, many of which users do not reflect upon. This requires a new perspective for product research.

Research Perspective and Descriptive Language

Bruno Latour and his “Reassembling the Social” significantly altered many people’s understanding of how we should study and describe society and processes within it. Latour talks a lot about how we should map the social landscape. In Actor-Network Theory, the subjects of society become not only people but also everything around them.

Is there a big or small difference between a woman driving, slowing down near a school when seeing a yellow “no more than 30 mph” sign, and a driver slowing down to avoid damaging his car’s suspension, which is at risk of hitting a “speed bump for speedsters”? The difference is big because the first is motivated by morality, symbols, road signs, the yellow color, and the second by the same list, with the addition of a thoughtfully placed concrete slab. But the difference is small because both are obeying something: the first is obeying infrequently manifested altruism: if she hadn’t slowed down, her conscience would be tormented by the moral law; the second is obeying considerable self-interest: if he hadn’t slowed down, his car’s suspension would have been damaged by the concrete slab. Should we say here that only the first attitude is social, moral, or symbolic, while the second is objective and material? No. But if we say both attitudes are social, how can we justify the difference between moral behavior and suspension springs? Relations may not be social throughout the whole process, but they are certainly brought together or connected by the engineers who designed the road. One cannot call themselves a sociologist and follow only certain relationships — moral, legal, and symbolic — stopping as soon as some physical relation is involved. That would make any research impossible.

– B. Latour, “Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory”

We must not lose sight of anything. Every little thing, like a trash bin or a door, can influence our practices and behavior. As researchers in digital products, we must study how people produce their practices, and in our perspective, digital products and devices must be treated as subjects of interaction just like people.

At the beginning of my article, I mentioned that it’s easier for me to turn on the heater in my bedroom with my phone because I’m usually already holding it and don’t want to switch my attention to the remote control lying nearby. It seems like a logical conclusion — the closer the objects to each other, the easier it is for us to interact with them. But that’s not true!

Consider the reverse example. When I need to quickly switch between two browser tabs, I separate them into two different windows. It seems like switching windows is an extra operation, but tabs were invented to avoid wasting time switching between windows. However, I already switch between windows constantly, and the “alt+tab” combination is ingrained in my subconscious, so it’s faster for me to switch between two windows than between two tabs in the same window. Describing this pattern would be impossible without understanding the system’s properties and how switching happens. Hotkeys and how they work are also a part of the interaction. I use this feature not because it is more convenient in a vacuum, but because it better fits into my usual pattern of computer use in this specific operation.

To properly use this perspective, we also need a slightly different approach to research. Among product researchers, it is largely understood, so much so that it seems obvious to us. But I think it’s important to say it again. The main method in our work is not interviews, but observation. Even when we talk to someone, we observe their responses and make conclusions based on our observations. The same applies to JTBD. The milkshake case is possible not because we asked the clients correctly, and the clients answered correctly. It became possible only due to a clear and, most importantly, detailed description of the pre-work snack practice. This description wouldn’t have been possible without observation, and in the description of this case, it’s evident — first, the specialists stood in the parking lot and observed who bought what and in what situation. Then they talked to people to understand why it happened that way. The best JTBD research, the best research for innovation — is observation.

Future Perspectives

Ideally, it would make sense to turn to the more academic environment here. Because ethnomethodology of digital product use would be incredibly useful. But unfortunately, there aren’t many works on this subject. Digital ethnography is now more focused on analyzing digital artifacts of human activity, not on how they produce that activity. Therefore, we will likely have to reflect on the experience of using digital products ourselves through the lens of Actor-Network Theory. This is what I encourage everyone to do.

Let’s strive to map our users' practices as thoroughly as Latour advises. The process of using a digital product is very complex and multifaceted, yet we are currently oversimplifying it. And the chain “find an image on Google, copy it, clean it from watermarks, crop it in Photoshop, then insert it into a PowerPoint presentation” turns into “add an image to the presentation.” It is in the detailed study and description of the practices of using digital devices and products that lies the key to creating successful innovations. Detailed descriptions of practices are key to successful exploratory research.

As long as we continue to perceive our research simplistically and innovation as a revolution, we will be doomed to develop our products literally by trial and error. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, especially given that modern development frameworks now aim to reduce the cost of failure. But if we are to engage in research, let’s do it as effectively as possible. The more observational elements there are in our research work, the more useful our insights will be. The more the approach to innovation is focused not on producing a revolution but on embedding our product into familiar patterns, the more useful our products will become.

If you liked the article, feel free to share it, leave your comments and feedback at mail@uxrozum.com, or on telegram.